science fiction... (Page 8)

for a complete alphabetical list of ALL reviews start here

A

- B - C - D

- E - F - G

- H - I - J

- K - L - M

- N - O - P

- Q - R - S

- T - U - V

- W - X - Y - Z

Star Lord 2014 (SC

TPB)

see my review here

Starslammers

1983 (SC GN), 64 pgs

Written and drawn by Walter Simonson.

Colours: Louise Simonson, Deborah Pedler. Letters: John

Workman. Editors: Al Milgrom, Mary Jo Duffy.

Rating: * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 2

Published by Marvel Comics in over-sized tabloid format.

Space opera about a planet of elite inter-galactic mercenaries who had been an oppressed people, and now use their new calling (and the money and weapons they collect as payment) as preparation for going to war with the planet that had oppressed them.

If you ever thought "Star Wars" was too jingoistic and warlike, then you'll definitely hate The Starslammers. Walt Simonson, whether reflecting his own philosophy or just escapist entertainment, indulges in a kind of macho diatribe that, frankly, seems weird and even uncomfortable in the latter part of the 20th Century. The story's peopled by Macho-He-Men (and He-Women), talking about "true men", where human worth seems literally to be measured by an individual's fighting prowess. The "heroes" are mercenaries whose greatest dream is to commit genocide against their (admittedly sleazy) enemies.

The plot seems more of a build up to a story than the story itself. The characters aren't well defined, or even memorable, and the overall results cold. The story takes itself too seriously, lacking any kind of swashbuckling jauntiness that would, at least, make the Starslammers fun on a non-think level.

Still, if all that sounds like fun, Walt Simonson is certainly a fine artist and a competent, if unexceptional, dialogist. Simonson later returned to the premise a decade later with an (ultimately unfinished) mini-series set, apparently hundreds of years later (meaning it's not really a direct sequel).

The Starslammers was published in oversized, tabloid format

as a Marvel Graphic Novel.

Swords of the Swashbucklers 1984 (SC GN) 64 pages

Written

by Bill Mantlo. Illustrated by Jackson Guice.

Written

by Bill Mantlo. Illustrated by Jackson Guice.

Colours: Alfred Ramirez. Letters: Ken Bruzenak. Editor: Archie Goodwin,

Mary Jo Duffy.

Rating: * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by Marvel Comics (graphic novel #14) in over-sized tabloid format.

On modern earth, a spunky young girl uncovers an ancient alien device on the beach which sends out a signal...CUT TO: a distant galaxy where a race called Colonizers goes around, well, colonizing unsuspecting planets. The only force that stands up to them are pirates who are only marginally better, ethically speaking. Chief among these pirates is Raader, a half-human/half-alien lady pirate, and her multi-species crew who pick up the mysterious signal from beyond the "space cloud" where no ships have ever gone before. Or so they thought.

The intent here was to unapologetically transpose a pirate saga into space, married with the usual (and usually problematic) wish-fulfillment element of a human teen-ager thrown in -- a teen who, because it's a comicbook, and comics are ruled by superheroes, develops a superpower. I don't object to the idea of space pirates, but by plopping the idea so literally into the science fiction milieu (right down to the space ships looking like sailing vessels and the pirates brandishing swords while uttering lines about "me hearties") there's a feeling of: why bother? Why not just do a pirate comic -- something which has rarely, if ever, been tried before?

Swords of the Swashbucklers led into a 12 issue mini-series and, frankly, that intention shows...rather to the detriment of this graphic novel. As a stand alone work, it's not much. Most of the questions that are introduced over the course of this book are left unanswered by the end, and writer Bill Mantlo and artist Jackson Guice seem sufficiently preoccupied with just introducing the relevant elements (the premise, the main characters), that they don't put much effort into crafting an interesting story in and of itself. There're a couple of battles, a visit to the pirate world, etc. But everything's workmanlike at best. There're no scenes that, after the fact, make you go, "Gee, wasn't it cool when...?" When Raader's ship, the Starshadow, breaches the ominous and mysterious space cloud...well, nothing actually happens.

This is less a story than the bare bones of an idea. It's the sort of thing you pitch to your editor, but should embellish upon long before publication.

This was created by Mantlo and Guice, who, I believe, collaborated in the later days of the old Micronauts comic. In an afterward we're given the impression they were keen to do it. Which is a sad reminder that just because something is close to one's creative heart, doesn't mean it'll be one's best work. The writing is a tad bland, the tempo weighed down with kind of pointless captions that often reiterate what we can easily glean from the pictures and the dialogue, and are written in a flat manner, to boot.

Guice's art is O.K., but likewise a bit flat and it never really enlivens the characters...not that there's much characterization to illustrate. It doesn't help that, though the colours are beautiful, there seems to have been a problem with the printing process, often causing the colours to be a millimetre over from where they should be. Though Guice does throw in a cute visual in-joke, with one of the pirates in the background looking like Cerebus the Aardvark.

Ultimately this is a story in which we continually observe the action, but the writing and art never quite draw us into it. There's not much plot or characteriation in what amounts to a teaser for a subsequent mini-series.

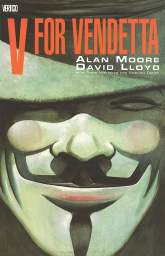

Written by Alan Moore. Illustrated by David Lloyd, with

Tony Weare.

Colours:

David Lloyd, Siobhan Dodds. Letters: various.

Colours:

David Lloyd, Siobhan Dodds. Letters: various.

Reprinting: V for Vendetta #1-10 (parts of which were first published in Warrior Magazine in 1982-1983)

Additional notes: intros by Moore and Lloyd, afterword by Moore.

Rating: * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 2

Suggested for Mature Readers

Published by DC Comics/Vertigo

Set in the then future -- the late 1990s -- V for Vendetta takes place in a fascist England after most other countries have been devastated by nuclear war. The fascists took over when things were bad and have managed to restore a semblance of order -- but one where all minorities and "undesirables" have been disposed of in Death Camps.

Evey is a teen age girl who, desperate to augment her meager living, clumsily turns to prostitution. But her first would-be client turns out to be an undercover cop (a "finger" man -- branches of authority are designated as body parts: the "ear" are eavesdroppers; the "eye" surveillance, etc.). He and his squad, having complete discretion in such matters, intend to rape and then execute Evey...until V shows up. Dressed in period clothes and wearing a white face mask that evokes the notorious English would-be anarchist of centuries before, Guy Fawkes, V is an enigmatic, possibly unstable figure. After rescuing Evey from her would be attackers (by killing most of them) he then symbolically blows up the parliament buildings (succeeding where his historical counterpart failed) and takes Evey under his wing.

Then he proceeds to carry out his vendetta against the government, with the authorities quickly realizing they're dealing with a terrorist/rebel -- and one who seems cleverer than they are.

Such is Alan Moore and David Lloyd's mature readers, science fiction drama, V for Vendetta. Although Alan Moore has gone on to become one of comicdoms most respected writers, V for Vendetta was actually one of the earliest things he wrote professionally, originally serialized in the British comic Warrior (Warrior was discontinued, leaving the series in limbo for a few years before Moore and Lloyd were allowed to finish it by American DC Comics). And it's a sign of things that were to come that V for Vendetta is still highly regarded -- and not merely as a fledgingly effort. Some people have claimed it's the best thing Moore wrote, even better than his highly esteemed The Watchman.

And V for Vendetta is good in spots -- very good. But it promises more than it quite delivers.

Originally serialized in short chapters of around eight pages, Moore is as much interested in exploring his world and his large cast of characters as he is in unfolding a plot. The cast involves Evey and various characters in the government, as well as Finch, a nominally decent cop who only supports the current order because the alternative, he fears, would be worse. V himself remains enigmatic, perpetually hidden behind his mask, speaking in cryptic riddles. The book is divided into three sections. The first details V assassinating various government officials (Evey's a bit put off by this, feeling murder isn't something she can condone). That section delivers an intriguing twist when the cop begins to suspect that they've read it all wrong: V isn't killing as political actions, he merely wants it to look that way. Instead, he's killing people who might, potentially, have a clue to who he really is. In other words, the assassinations are just covering his tracks, preparatory to starting on whatever his true plan is.

It's an intriguing twist, hinting that V has secrets he really wants concealed, and a massive plan yet to be unfolded. But, as mentioned, the book promises more than it delivers.

In some respects, I'd argue Moore's aptitude isn't really for linear plot. He can juggle large casts and weave a multi-facted tapestry, but I'm reminded of The Watchmen in which a framework story, of superheroes investigating someone trying to kill them, was just an excuse for exploring the characters and their world. Likewise, with V for Vendetta, Moore goes off in his eight page, bite size chapters, spreading before us his vast cast of characters, and their frailties...but to the point where V disappears for whole chunks of the story. When V does act, his actions often seem simplistic, his great plan vague.

V announces he's giving the population two years to shape up...or else, as if Moore is hinting at a master plan. Yet the story climaxes only a few months later. It's as if Moore is promising the story is headed somewhere...but forgets where. Likewise, for all that V goes to such great lengths to conceal his identity, it's unclear how things would have changed if the government did learn who he was.

It's difficult, in SF, to establish as your premise a fascist reality...and then have your lone wolf hero bring it down. After all, fascist governments don't usually fall that easily. So I can understand Moore's reliance on simplistic solutions, or setting up a system with a ready made Achilles' Heel. Moore even goes to the trouble of establishing that V, victim of government experiments years before, has super abilities...without bothering to detail what those abilities might be. It's just a way of allowing Moore to undercut any objectors who might say, "How can one man bring down an entire government? How can he set bombs in impenetrable buildings?"

"Why, he's super powered," Moore might respond.

"Yeah, but what does that mean?" the detractors might insist. "Is he super smart? Can he fly? Can he walk through walls?"

"He's just, y'know, super."

"Yeah, but in what way?"

"He just is."

"Is what?"

"Oh, shove off!"

The surface level plotting ends up seeming kind of vague and unsatisfying. In his afterward, Moore suggests that there was an element of he and Lloyd winging it, of the story taking them in unexpected directions. Which seems like a polite spin on saying, they weren't quite sure what to do with their ideas. And it shows. Many of the chapters, looking in on the various characters, can feel a little like place holders. As if Moore and Lloyd weren't always sure what to do next, story-wise, so they said, "Hey, let's just look in on so-and-so this week -- that'll help kill a few pages."

A problem with the emphasis on the characters over the suspense-adventure plot is that the characters aren't fully realized. In fact, it was actually hard to keep track of them at times, as it wasn't always clear who was who (Lloyd's art doesn't always clearly distinguish the personalities either). And like with some of Moore's other works, he seems more interested in defining characters by specfic quirks or neurosies (the Leader having a psycho-sexual infatuation with his computer!), rather than successfully making such charactertistics seem part of a well rounded human being. I liked the notion that the story is as much about revealing this world through people who inhabit it as it is through anything else. But I just didn't always find myself sold on, or interested in, the characters.

And what of the reality itself? Moore himself admits that, regarded years later, there's a certain naivety to the basic assumptions of the story, like that England could emerge, relatively unscathed, from a nuclear war. By establishing such a traumatic event, it mutes some of the political bite (as opposed to a story where the slide into fascism was more gradual, more natural). However, I enjoyed the very Britishness of the fascist state, where the characters aren't stiff-armed Nazis, but rather civil...even as they oversee a monstrous regime.

At the same time, it could be argued that Moore's gentle fascism actually dilutes the impact of his story. I've often argued Moore's stuff can seem more cerebral than visceral, as if he's intrigued by concepts more than the reality. When a character reflects regretfully on the purges that eliminated England's minorities and homosexuals, the character thinks how much more vibrant and colourful was the old England. Fair enough, to regard such purges as a loss for England as a society. But Moore focuses on the abstract, rather than the gut wrenching, mind shattering horror of genocide, of millions being murdered simply for being who they were! Moore intellectualizes what should resist all efforts to be processed by the civilized mind. When a character visits the wreck of an old Death Camp, it should leave you shaken. But, frankly, it didn't.

The best realization, emotionally, of these themes involves a note left by a camp victim, though even then, it actually reminded me of a better, heartbreaking, EC Comics tale by Wally Wood from decades earlier.

At first, Moore seems to want to play with ambiguity. Is V the hero, or is he just another sort of villain? It's an intriguing, challenging idea (asking just how far is too far in fighting tyranny). But Moore actually seems to lose that idea (if indeed it was there) as he goes, with V later seeming the voice of wisdom and reason. Which, given how mad and ruthless some of his actions are, is actually more troubling.

By the third and final section (written, apparently, a few years after the earlier parts) Moore seems to have gone in two directions. On one hand, he cranks up the soap opera, emphasizing the machinations and double crosses among the elite. On the other, he actually jettisons some of the pretense of narrative, as he seems to be using the story -- and V -- as a mouthpiece for expressing political ideologies, pontificating on the nature of Anarchy (as distinguished from chaos). Some of these sequences can become particularly dry, as Moore expounds upon, at times, ill-defined philosophies, and playing them out in an ill-defined way. This future England is not entirely convincing as a political structure, so that its dissolution is not entirely enlightening as a blueprint for how we might tackle real world problems. By the end, all V has created is chaos (as opposed to anarchy) and Moore leaves it vague as to how things will improve.

I've also commented before that, if one wanted to, one

could infer a strangely misogynistic streak to some of Moore's work...and

V for Vendetta proves no exception. Not so much for the first part. Whatever

hardships Evey endures are reasonably justified by the narrative, and Evey,

is, after all, a protagonist. But in the later part, a female character

who'd previously barely warranted a few lines, is suddenly repositioned

as almost the principal villain of the saga, shrewishly humiliating her

husband even as she plots her own coups, and whose final comeuppance is

distasteful and degrading. Honestly, I'd half wonder if Moore went through a bitter divorce or something between the writing of the second and third sections of the story. But then, even the fact that the male Leader is given

a curiously feminine surname (Mr. Susan) is suggestive.

It's perhaps interesting to remark on the fact that I generally liked the story up until the third and final section. And when they did the big budget movie adaptation, they remained -- relatively -- faithful to the source material, but then start to diverge away from it more noticeably toward the end, as if they too felt the original series began to lose its way.

Lloyd's art is mostly quite impressive and effective, with understated realism that lends credence to this future tale. At the same time, the art can also be a bit overly dark and muddy at times (it was originally presented in black and white, but here has been coloured). It adds to the dark atmosphere (without seeming heavy handed), but it can make it hard to tell what's going on at times. Occasionally Lloyd's composition is a bit off (doing a close up of a face when we need to see what's in a character's hand) and, as noted, the art, combined with Moore's script, doesn't always succeed in distinguishing characters, which is awkward given that the characters are sometimes more important than the plot.

The TPB collection includes various extras: brief intros by Moore and Lloyd; and an extensive afterward by Moore, written at the time of the series' original serialization, that gives some intriguing insight into the series, and into Moore himself (at the time), who writes in a friendly, funny way. There are also a couple of short pieces that are part of the series, but more like sidebars. One inparticular, "Vincent", demonstrates a weakness with the decision to tell the story mainly in pictures and dialogue (with a minimum of text captions or thought balloons) in that I wasn't entirely sure what the point was (or what the character's motivation was).

The bottom line with V for Vendetta is that it starts out well, and I certainly liked aspects of it. It is worth reading, but there's a sense Moore and Lloyd tackled a bigger topic than they could comfortably handle.

Ironically, had Moore and Lloyd never completed it after the forced hiatus with the cancellation of Warrior, I might have enjoyed it even more. The first part is definitely strongest and we could've been left to fantasize about its unfulfilled greatness -- like V himself: forever masked and a glorious enigma

Wake, vol. 4 / 5 : The Sign of the Demons 2003 (SC TPB) 96 pages

Written

by Jean David Morvan. Art and colour by Philippe Buchet.

Written

by Jean David Morvan. Art and colour by Philippe Buchet.

Letters: Ortho. Translation: Joe Johnson.

Originally published in 2001 in Europe

Rating: * * * * (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by NBM Publishing

Suggested (mildly) for mature readers

Wake is a European graphic novel series -- now being re-published in English by an American company -- that can be seen as a bit of a hybrid of Star Trek/Star Wars. The setting is an armada of spaceships cruising through the galaxy, looking for planets to colonize or otherwise contact. And though ostensibly benevolent, there is corruption on board (as evidenced in one of the stories here). The inhabitants of the armada are multi-species, but the central heroine is Navee, a spunky human -- vaguely North American Indian -- but who seems to be the only human in the fleet (a mystery that, presumably, both she and the reader will unravel as the series evolves).

NBM Publishing had started out releasing English translations of each 46 page graphic novel but, either because they were falling behind, or perhaps for sales reasons, with this volume started publishing two stories per volume. The first story (#4) "The Sign of the Demons" and the second (#5, whose title is written in an alien script and so can't be reproduced here).

The first story in this collection has Navee and some compatriots arriving on a primitive planet, looking for some observers who were sent ahead of them but have gone missing. The planet is in the throes of a revolution, as a slave class has risen up against the ruling species, and our heroes get embroiled in it...and learn of a sinister conspiracy in their own fleet that has been exploiting such worlds in the past.

I'll confess, I've had some mixed feelings about European (and non-North American comics in general) that I've read over the years. For all that fans of them often cite them as more sophisticated, more mature than American comics, I often don't feel that way. Worse, not only have they often seemed shallow and thin, but many times have a smary, sophomoric sense of "humour" and a "sense? who needs to make sense?" approach to plotting. But this turned out to be an enjoyable adventure. It's coherent, with a nice mix of larger-than-life comicbooky action, and light-heartedness, with some genuine character detail and serious undercurrents. It's briskly paced, and just complex enough -- in story and character development -- to adequately justify its page count.

There's even a cute, if problematic, idea that some of the planet's inhabitants talk in a way where their dialogue is spelled out phonetically...meaning you sometimes have to sound out a word balloon in order to "hear" what they're saying.

The art has a certain manga influence, with a cartooniness, and Navee as a perky, big eyed heroine. But it's effective and expressive, keeping a jaunty tone and, given the series' emphasis on non human looking aliens, serves the needs of the different species. The backgrounds are beautifully detailed with an at times extraordinary sense of perspective that really makes the vistas seem huge, and Buchet often employs panoramic angles that really make a waterfall, or a sprawling city, fairly leap off the page. The bold, cheery colours help, of course, as does the fact that it's printed in an oversize format that really shows off the art (Buchet often employing 10 or 12 panels per page). Oh, why mince words? The art was enormously attractive and helps to let you lose yourself in this alien environment.

Though a peculiarity of the lettering, which I'm guessing is a result of translating the dialogue into English (and therefore, employing different numbers of words) while employing the original word balloons, is that the size of the words can vary from baloon to balloon

The second story goes an even more political route involving an underclass of aliens aboard the Wake itself who have begun suicide bombings to draw attention to their plight. Naveen becomes involved when they try to kidnap her to blackmail the governments into providing them greater aide. And Naveen begins to sympathize with the terrorists.

It's an interesting, probably controversial story, to craft a tale that is so clearly meant to show the human/sympathetic side of terrorists (even as the writer is not endorsing their actions). It's an ambitious notion...even as the issues are maybe simplified. By making the Ftoross mainly an economic underclass, fighting to end their poverty and disease, Morvan avoids the more complicated dilemmas that are posed by many real world terrorists, whose actions are often motivated by religious and racial factors. Yes, one could argue it's only the systemic poverty and hopelessness of such groups that makes them prey to religious demagogues who twist things into religious and ethnic strifes. But the fact of the matter is, it might be harder for Naveen (and the reader) to empathize with the Ftoross if they, say, wanted death for all heretics, or preached genocide against another ethnic group as such real world terrorists often do. Of course, one could argue that I'm simplifying, as some observers would argue there is a difference in motivation between, say, Palestinian suicide bombers and other Islamic fundamentalist terrorists.

Anyway, the story is well told and well paced.

By telling a self-contained story, each in 46 pages (with lots of panels) Morvan and Buchet have crafted two well told, interesting stories, deftly mixing fun and light-heartedness, with seriousness and even poignancy. For fans of science fiction TV series like the various Star Treks, Wake will be a welcome experience. With breathtaking sets and scenery, and weird and diverse aliens, this volume of Wake seems like a couple of episodes of a TV series -- a TV series with an unlimited budget and special effects, with effective and appealing characters, and an intriguing reality against which the stories can be set.

Visually appealing, and highly entertaining, Wake is quite enjoyable. In fact, it's easy to get dragged along in its wake (oh, I couldn't resist).

Xenozoic Tales, vol 1: After the End 2003 (SC TPB) 160 pages

Written

and Illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Written

and Illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Black and white. Letters: unbilled.

reprinting: Xenozoic Tales #1-6, plus a story from Death Rattle #8 - 1986-1988, originally published by Kitchen Sink

Additional notes: intro by paleontologist Philip Currie; sketchbook.

Rating: * * * * 1/2 (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Published by Dark Horse Comics

Suggested (mildly) for mature readers (violence)

Xenozoic Tales is set hundreds of years in the future, after one of those ill-defined apocalypses that arise in science fiction. The world is now comprised of human tribes, still living much as we do now -- with local governments, and people dressing in familiar styles -- but in the wreck of the ancient cities, with much of our current technology lost to them. Oh, and dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures roam the earth. And that's the gist of the series: people living with dinosaurs. But not the friendly dinos of, say, "Dinotopia", these are wild beasts, best avoided for the most part.

The protagonists are Jack "Cadillac" Tenrec, an iconclast who ruffles the tribal government's feathers even as they often call upon him to save the day. He acts as a guide, policeman, and all around trouble shooter when he's not in his garage, retooling classic 20th Century cars. Jack is also something of a self-styled shaman, very much into an ecological, balance-of-nature philosophy. His chief foil is Hannah Dundee, an ambassador from another tribe, very much Jack's equal, and the two bicker so much, you can't help but assume, in true narrative tradition, that they'll eventually end up together.

Mark Schultz's well-regarded comic book series has risen again and again, not unlike the prehistoric creatures that people its pages. Originally published by the now-defunct Kitchen Sink Press, the original issues were later published as Cadillacs and Dinosaurs -- in colour -- by the Epic line of comics (an imprint of Marvel Comics that I think has long since been discontinued); Schultz also licensed it to the short-lived Topps Comics, to produce a series (also under the title Cadillacs and Dinosaurs) by other creators. Hmmm. There seems to be a pattern of mass extinction involving comics companies that publish the series. Dark Horse had better watch out, because it has recently released two TPBs collecting the complete original series in black and white (volume two is reviewed below). Along the way, the series also was turned into a network cartoon -- short-lived.

So why has a series that only produced a little over a dozen issues more than fifteen years ago enjoyed such periodic resurrections?

'Cause it's a lot of fun.

It's clear pretty early in this first of the two volumes that Schultz has a creative vision firmly in his mind. Xenozoic Tales is an unapologetic mix of old and new, of nostalgia and New Age. It's set centuries in the future, but characters dress in safari suits like out of a Jungle Jim comic strip and cruise around in classic 1950s cars. And what exactly is the scientific rationale behind dinosaurs walking the earth? If questions like that bother you, move on. But Schultz isn't just writing and drawing an adventure series...he's writing and drawing an adventure series that seems like the sort of thing we all would've read growing up, but never did. Schultz's art style even borrows from classic past masters like Wally Wood and a bit from Al Williamson (not to mention later talents like Berni Wrightson with his feathery inking). With the evocative illustrative style, Xenozoic Tales kind of seems like it might've been an old EC Comic. Rough n' ready, gruff Jack Tenrec is a pure 1950s hero, and ballsy Hannah is just the kind of foil you'd expect for him.

There's a hint of cartoony exaggeration early on (burly guys' shoulders seem a bit too broad, jaws a little too jutting) but that becomes less as Schultz refines his style. Throughout, Schultz, who was fairly new to comics at the time, shows a surprising eye for just telling the story with his images. The pictures can be striking, moody, artfully rendered, but above all, they serve the narrative, not the other way around. Perhaps also reflecting an EC influence, some of the stories are unnecessarily gory -- unnecessary in a series that is otherwise fairly family friendly, with little cussing or sexuality. Though, even then, the violence often feels more explicit than it really is -- a lot of black ink blood when a dinosaur attacks. And Schultz seems to move away from the violence as the stories progress, with the most, uh, gooiest story being the very first published (in a horror anthology called Death Rattle) though it's inserted in the middle of this collection.

Just as an aside, Schultz -- as a writer -- would later team up with venerable Al Williamson to produced an entertaining, two-issue Flash Gordon mini-series for Marvel Comics.

There is an unpretentious simplicity at times, which Schultz freely owns up to by the fact that some of the stories are only eight or ten pages long. Instead of stretching something out beyond its interest, he knows when to close the curtain on a particular idea. As such, Xenozoic Tales can subtly weave a panorama of this fanciful reality, with stories veering from man-against-man, to man-against-nature, to others that are more like dramas. When assembled together, these 12 stories benefit from each other. No one story is, perhaps, a stand out, but none are bad either. With no story expected to sink or swim on its own, the book becomes a fun read as you cruise from one enjoyable tale to another.

And just as you begin to become seduced by the intentionally old fashioned feel, the simplicity to some of the plots, you realize that there's a subtle sophistication lurking under the surface that probably wouldn't have been there in a real 1950s series. Though not given to brooding introspection, both Jack and Hannah begin to emerge as vividly realized, even believable, people, with foibles as well as virtues (albeit supporting characters are not as well defined). And the plots can evince a nice craftsmanship; the stories may not be especially complicated, but Schultz lets them unfold in a way that keeps you turning from page to page. There are also hints of an overall story arc, involving learning about the disaster which occurred centuries before, and a mysterious race of humanoid dinosaurs. But whether such threads ever paid off, I guess I'll have to read the next volume to see.

Perhaps most surprising is the series' increasingly explicit enviromentalism that lets you know that, beyond the "gee whiz" adventure, Schultz is trying to say something.

What sticks with you most about Xenozoic Tales is simply the milieu itself. Beautifully rendered by Schultz, even in black and white, the jungles are lush, the city craggy and gothic, the dinosaurs carefully rendered; the men are rugged, the women pretty. Perhaps reflecting its nostalgic roots, even when Schultz indulges in a little salacious cheesecake -- such as a sequence where Jack and Hannaah go fishing, and Schultz presents Hannah in a few blatantly fetching poses -- she's still dressed rather demurely in a one-piece bathing suit. Oh, well, he can't get everything right!

Fantasy fiction is very much about escapism...and who of us hasn't fantasized about a world of prehistoric dinosaurs, where the concerns of our everyday lives are no longer relevant? Welcome to the Xenozoic era...you just might want to stay awhile.

Xenozoic Tales, vol. 2: The New World 2003 (SC TPB) 176 pages

Written

and illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Written

and illustrated by Mark Schultz.

Black & White. Letters: unbilled

Reprinting: Xenozoic #7-14 (1988-1996)

Rating: * * * 1/2 (out of 5)

Number of readings: 1

Additional notes: intro by Frank Cho; afterward by Mark Schultz; sketch gallery.

Mildly suggested for mature readers.

Published by Dark Horse Comics

This is the second of two volumes (the first is reviewed above) published by Dark Horse comics collecting, in its original black and white, Mark Schultz's well-regarded, off-beat adventure series Xenozoic (also known as Cadillacs and Dinosaurs). Set hundreds of years in the future, after vague cataclysms have destroyed civilization, it follows the adventures of human "tribes" -- mixing aspects of pre-industrial and industrial societies -- in a jungle world repopulated by dinosaaurs. It was originally published by Kitchen Sink Press and has been reprinted by other companies -- the latest being Dark Horse.

The stories in this collection are more accomplished, more ambitious, than those in the first volume, and Schultz's art even more breathtaking and impressive -- yet the overall result, though good, is perhaps more disappointing. For one thing, Schultz has dropped the flexible story length of the early issues -- where a story might run anywhere from 8 to 28 pages, which permitted a lot of variety in the types of tales he told, chronicling the exploits of Jack Tenrec and Hannah Dundee and their colleagues. This time out, he's settled on conventional 22 pages per story. And while the early stories could be deliberately episodic, occasionally focusing on a peripheral character rather than Jack or Hannah, delineating this strange new world, here Schultz is more focused on unfolding a story arc. It's not so much that each issue is "to be continued" in a cliff hanger way, but each issue leads to the next, as Jack's iconoclastic nature finds him increasingly ostracized from his own government, eventually having to flee the City in the Sea with Hannah to her tribe, where he gets caught up in other machinations.

Also problematic is that the saga is left unfinished. Oh, there are no cliff hangers, no final issue revelations that leave you dangling. But throughout these issues Schultz weaves hints of a bigger story, or grander themes, and even on the surface there is the saga of Jack and Hannah fleeing Jack's home, then plotting to retake the city from those who exiled him. But the series ends before that can happen.

Schultz, in his afterward, insists he will finish it...someday. And maybe he will. But excuse my scepticism. After all, it's been a number of years, and Schultz has yet to produce any further issues (and he even briefly licensed the property out to other creators under the Cadillacs and Dinosaurs name). And the story threads themselves seem sufficiently amorphous that I could well imagine the reason Schultz has been blocked...is because he's not sure how to tie it all together.

With all that being said, this second collection is still entertaining. Schultz's beautifully shadowed, lush and lavish artwork is, at times, stunning to look at, and has come a long way from the earliest issues (though they were still nicely drawn themselves). And the premise remains irresistible. There's a lot of ambition -- both character-wise and philosophical -- at work in the series, deceptively so, that can be quite impressive. Though, as such, there's a little less emphasis on just the good ol' "Boys Own" adventure aspects that were more pronounced earlier. Though there's still adventure, running about, human villains and fearsome dinosaurs -- there's not as much of that as you might want.

Schultz's handling of the Jack/Hannah relationship is a bit bumpy. I liked the subtle way Schultz was developing the relationship in the early issues, slowly developing a romantic undercurrent without drawing attention to it. This continues that approach, where it's almost a romance, without either character acknowledging it. Except, then, Schultz suddenly accelerates the relationship with the characters falling into bed with each other...when I still thought they were at that "sexual tension" phase. Stranger still, the next issue, they seem right back to being more friends than lovers, as if the physical tryst was a hasty plot point rather than a natural development!

The New Age is an entertaining read and, in many respects, is a more accomplished collection (particularly art-wise) than the first. But the first remains the more entertaining, and remains probably the volume to start with.

BACK TO < SF Page Seven