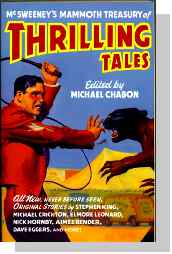

One of the earliest editorials which I contributed to this webzine

was a review of McSweeney's Mammoth

Treasury of Thrilling Tales. A not very favourable

review.

I did not like the stories found therein. In fact, I still keep

that anthology lying out in the middle of my bedroom floor just so I

can give it a good swift kick when I'm feeling particularly

pissed.

Mammoth

Treasury of Thrilling Tales. A not very favourable

review.

I did not like the stories found therein. In fact, I still keep

that anthology lying out in the middle of my bedroom floor just so I

can give it a good swift kick when I'm feeling particularly

pissed.

But my main complaint wasn't with the stories, exactly. To be

sure, I hated them one and all, but I also recognize that many readers

enjoy those sorts of stories and more power to them. No, my

complaint was with the simple fact that, for an anthology called

"Thrilling Tales", NONE of the stories came CLOSE to being

THRILLING! If they had simply tried and failed, again I wouldn't

have been so peeved. But who's kidding who? The

authors clearly had listened impatiently to the guidelines, nodding

every

now and then, maybe throwing in the odd "I getcha, sure" -- and then

they

went home and wrote exactly the sort of Art House stuff they always

write. Some joke. How they must have laughed.

Please understand, it wasn't just the promise held out by that Pulpish

title (and cover!) that, encouraging so much, led to my

disappointment.

Rather, it was the fact that the entire project was

supposed to have been conceived as a grand experiment to recapture what

short fiction --

specifically genre short

fiction --

had lost starting some time around the

1950s. At least that was the claim of the editor, Michael Chabon,

in his introduction. And, unlike lowly dung beetles such as myself, when

Michael Chabon says fiction has lost something, he is not so easily

dismissed.

The Pulitzer Prize winning author of The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier

and Klay, Chabon is himself a purveyor of the kind of high-brow,

intellectual

fiction whose existence he was now lamenting. Something, he felt,

had been lost in the art of short story writing, and he was as guilty

as anyone. Where once Fiction was about plotted stories

where exciting things happen and great deeds are done, Fiction today

had become

dominated by "quotidian, plotless, moment of truth revelatory" tales

"sparkling with

epiphantic dew". An opinion with which I largely agree -- and I'll look up "epiphantic".

So,

while I gave McSweeney's

Thrilling Tales a disgusted thumbs down for the stories, I

nonetheless said

that it was worth buying simply to hear someone of

Chabon's creds finally saying what we are all thinking.

Is that so much to ask? Apparently, yeah.

Flash forward. While recently cruising the Net, I came upon an

editorial at Science Fiction Weekly, the ezine belonging to the Science

Fiction Channel. There editor Scott Edelman demonstrated that

even a heavy-weight like Michael Chabon could indeed be dismissed if he

dared to speak the unspeakable. Edelman's reaction to McSweeney's

Thrilling Tales was the exact opposite of mine. He loved

the

stories to bits, but

was absolutely enraged by Chabon's introduction. Wrote Edelman:

"In his introduction, Chabon bemoans the supposed malaise into which

fiction has fallen these days, and longs for the days when short

stories didn't worry about epiphanies, but were just gosh-darn fun..."

You will note the phrase "gosh-darn fun". I think I am safe in

saying that Edelman is mocking the very stories which Chabon wishes to

recapture. Yes? Why then does he go on to argue that those

"gosh-darn fun" stories still make up the modern literary landscape,

that Chabon is tilting at windmills -- or, more specifically, straw men.

What are these GENRES, (Edelman wants to know), that Chabon thinks

have vanished? Who are these modern AUTHORS who, (Edelman asks),

aren't really enjoying the stories they are writing? And, most

importantly, who are these READERS, (Edelman furiously demands), who

are

"enduring fiction only as a

kind of self-flagellating penance, as if reading today were like being

forced to eat one's vegetables?" To these questions, Edelman

gives a resounding rejoinder:

"I don't recognize those writers or readers. They are straw men."

Straw men? An odd example of willful blindness, yes?

After all, isn't Chabon himself an example of one of those dissatisfied

reader/writers? Or doesn't Chabon's opinion count? Then I

can add at least one other name to that list. Or doesn't my

opinion count either?

Reading Edelman's editorial, I find myself wondering if he literally

doesn't understand what the question is. One minute he is mocking

the very notion of "thrilling tales", dismissing them as "gosh-darn

fun"; the next he is just as vehemently insisting such tales are alive

and well and living in a spin rack near you. Well, which is it

to be? Does he even understand what it is to sit back and read a

story for fun?

You can hardly surf

anywhere on the Net without running into a webzine with a "mission

statement" that reads something like: "I don't like the stuff that gets

published nowadays, and I started this webzine to fill a void."

Each one of those editors thinks they are

publishing something different from everyone else. Yet, for my

money, I confess I can't see the difference between them, or, for that

matter, the difference between those editors and the mainstream editors

they are rebelling against. The more they profess to be

different the more they just seem to be publishing precisely the sort

of stories which Chabon was railing against -- "moment of truth",

"plotless" stories "sparkling with epiphantic dew". Or as

I rather bitterly characterize them: "Art House stories".

What precisely do I mean by Art House stories? For starters,

there are stories which, once I reach the end, leave me baffled as to

what the story was about or what happened -- literally.

Okay, in some cases I'm probably just not sharp enough, I admit

that. But I have read plenty of stories which left me baffled

which, upon my reading a review by someone presumably smarter than

myself,

proved to be just as baffling to him/her. The only difference

between us being that the reviewer enjoyed being baffled, while I just

got pissed off. I do not like reaching the end of a story and

going "D'wah?" That's just the boy my mamma raised and I ain't

about to change.

Then there are other Art House stories not so easily defined.

Stories which have flamboyant trappings, or which seem to

fit into Pulpish genres, but which are anything but. Which is

precisely why Michael Chabon was able to publish an anthology called

"Thrilling Tales", billed as a supposed revival of Pulp Fiction, and

countless reviewers were suckered in, reviewing the stories as if they

really were somehow Pulp adventures. To use the example I used

when I reviewed this anthology the first

time: "Tedford and the Megalodon" sounds like it should be a rip

roaring Pulpy adventure. It's a story about a guy who goes

hunting a giant prehistoric shark, called a Megalodon. It has,

therefore, the trappings of a

thrilling tale, an exciting

adventure. Countless reviewers might compare it to Jaws.

They would see no difference between Benchley's novel and this short

story. Both feature big sharks? Someone gets eaten?

Well, what more do

you need?

Quite a bit actually. "Tedford and the Megalodon" depicts a

hunter, Tedford, spending the entire story sitting in his

kayak waiting for the shark to show up until, suddenly, the shark does,

and eats him. End of story. No conflict. No

action. No adventure. No problem solving. No

nuttin'. He just gets EATEN! This is not Jaws. This

is not "thrilling". This just pisses me off.

But what gets me, and the reason I am writing this essay, is that I

don't see why it should be so fecking difficult for someone like Chabon

to say the simple obvious truth. Nor, in doing so, why the wrath

of

God should be called down upon his head. Because, to be sure,

Scott Edelman

wasn't the only one

who took umbrage with Chabon's remarks. Amongst Art House

reviewers Chabon's words made like the fox in the hen house.

Feathers flew and the chickens were still attached. I couldn't

find anyone who came out on Chabon's

side, who had the courage to say, yes, modern genre fiction is no

longer about having fun.

But that is the bottom line, isn't it? Fun? Oh, I'm not

saying there aren't plenty of readers out there who have fun reading

modern genre fiction. Of course there are. But I do think

an awful lot of readers are

indeed reading those stories because they feel it's the thing to do --

"like being

forced to eat one's vegetables". And I think for every reader who

sincerely enjoys what passes for modern genre fiction there are

countless other sentient beings on this precious globe of ours who

don't read at all because they don't enjoy

what is being offered. Don't their opinions count?

The problem is that the sort of stories that judges give awards to

are rarely the sort of stories that most people like to read. And

I'm not saying that's wrong. Truth is, if I were judging the

Nebulas, I'd give the award to some complex psychological drama that I

would never have waded through if I wasn't

being asked to judge it. Then I'd go home and crack open a copy

of the latest Michael Crichton bestseller and read it all in one

sitting. Hypocrisy? Maybe. (Well, actually...

yes.) But those two markets are

incompatible. Either you write to win awards or you write to

please the readers. You must choose your master.

I know I have.

Jeffrey Blair Latta, co-editor and Supreme Plasmate

Got a response? Email us at lattabros@yahoo.com