I’m sitting one

morning in my small office in Aspen Colorado, where I live, when the

phone rings and it is Dino. The movie producer Dino De

Laurentiis, that is to say. His last name isn’t used much even by

total strangers, though some of his most immediate entourage tab him

“Mr. D.” Words aren’t wasted. “I give-a you jus’ a title, two

words, you tell-a me what you think.” Dramatic pause. “King-a

Kong!” “Sounds terrific,” say I. “Okay, you come-a down

tomorrow, we discuss it!”

So commenced my writing of the screenplay which is this book.

Some very simple folk imagine actors make up their own lines.

Some more sophisticated know that directors tell the actors what to

say. Both groups are seriously bananas.

Bit of background while I’m winging down to LA from Aspen. I’d

worked for Dino before on Three Days

of the Condor, which had recently come out with Robert Redford

and Faye Dunaway, and was thought to have turned out okay. If it

had turned out rotten you probably wouldn’t be reading my words here,

for in this business if a script of yours turns out rotten you usually

don’t work so quick for that producer again. That is as it should

be: it stirs the adrenaline, makes every page a fresh challenge, etc.,

etc. Actually, I had met Dino several years before, when he was

still Rome based but cooped up temporarily in a bungalow at the Beverly

Hills Hotel. We talked about a sequel to Barbarella, the comic strip sci-fi

fantasy Dino had produced starring a bare and non-political Jane

Fonda. All he really had for the follow up was a setting and a

terrific title. Much of the action was to be submarine, and the

title Going Down. In

those days before the full flush of the sexual revolution that title

was stunningly daring -- if not out of the question -- and for many

good reasons Going Down never went. The reason I was summoned for

it was presumably because I’d originated the TV version of another

comic strip, Batman. It

was the first thing I’d ever written for

film and was done while residing in Spain (1965) with wife and baby

kids, the somewhat banal idea being to live cheap and write a Great

American Play. Anyway. The next year found us all in

California, me a fledgling movie writer.

I had good luck. I worked steadily from the start. The

features I worked on in the ten years twixt then and now ranged from Pretty Poison (which lost lots for

Twentieth Century Fox but copped me a Best Screenplay of the Year from

the New York Film Critics) to a turkey called Fathom which starred Raquel Welsh

as a cryptic skydiver, and was so entirely without merit that even Ms.

Welsh’s drumbeaters omit it from her film bio. Other of my

credits were such as The Parallax

View (Warren Beatty), Papillon

(McQueen and Hoffman) and The

Drowning Pool (Mr. and Mrs. P. Newman). So much for

history.

Now my flight from Aspen is finished, and we rejoin King Kong as I enter Dino’s office

on North Canon Drive in Beverly Hills, an enclave so richly Italianate

that one expects a Borgia Pope to be working the Xerox machine.

We are about to have our first KK story conference.

A script writer friend of mine always says he’ll write such-and-such a

job for free -- but he’ll want $5000 an hour for the Meetings.

Larry is dead right. The Meetings one must endure in this game

are excruciating and soul numbing -- said torture increasing directly

as the square of the budget. Nobody guessed at the time that our

KK would weigh in at around $25 million, but obviously he wasn’t going

to be a cheapie. A writer might reasonably expect 100 hours or so

of talk on such a heavy weight before being unleashed to bang key and

ribbon.

Dino is different. Totally. Nobody experienced in flicks is

apt to believe the following paragraph, but I swear to God it’s

true.

My homework for the confab consisted of having run the original Kong a

couple of times in 16mm, projected on a sheet in an Aspen living room

heavily populated with kids. I assume Dino had done the same in

his Canon Drive projection room. So my first question that day

was should our remade KK be in the 1930s period of the original?

Dino thought not. Modern. I agreed. It followed

immediately that the story device of the original -- a two-bit movie

producer heading for the South Seas on a speculation scouting trip with

a gorgeous blonde actress -- had to go. Just too plain silly for today’s audience.

What to replace it with? “You think-a something, Lorenzo…”

I said I’d try and had just one other basic query: Should end still

have Kong blasted off New York skyscraper? Yes, said Dino.

We planted a couple of other guidemarks. Start with as much

reality as possible. Develop the love story between Kong

and the girl much further than it went in the original. (People

tend to forget, but Fay Wray’s behaviour with Kong in the old one is

something less than emotionally rich. Every time she comes out of

a faint, she SHRIEKS! Period.) Heaven knows how, but try to characterize Kong. Dino

capered around his office, pantomiming an enormous monkey plucking off

a girl’s vestments, delicately, as one would pluck the petals of a

flower. (Dino began his career as an actor.) That was the

entire content of our conference on how to remake King Kong. Fifteen minutes

after it began, I was leaving Canon Drive HQ en route back to Aspen to

write a story outline.

A producer friend, Jerry Bick, happened to phone me the next day about

another project. In the course of chitchatting he mentioned how he’d always wanted to redo KK, but

couldn’t nail down the rights. He didn’t know quite how he’d have

approached it, Jerry said, except he had a mental picture of a terrific

scene. Kong in a supertanker, one of those 1000-ft long behemoths

of the sea. Zap! Light

bulbs glowing above the noggin! I asked Jerry if I could

use that elegant notion and he said of course.

The basic story device immediately fell into place: oil company

expedition. In truth I’d been toying with that idea before my

gift from Jerry, and had even mentioned it to Dino as an off-the-cuff

possibility, but it was the supertanker image that locked it in.

I returned to Canon Drive a couple of weeks later with an outline --

some forty double-spaced pages of narrative. That is to say, I

returned to Canon Drive a few days after sending the outline down, for

it is a charming peculiarity of Dino’s that he has all written material

translated into Italian for his reading. All written material.

Outlines, scripts, whole novels. Dino rises before six every

morning and reads. Carefully. He is a disciple of the

written word. People who don’t know him well are often misled by

his flamboyant character, and confounded when he catches them out on

some tiny detail of the script.

My outline was well received. Re-reading those forty pages today,

I find them startling for two reasons: (1) How exactly they set the

style and story of the finished picture; (2) How totally

many of the details got changed. For example: Jack Prescott, the

Princetonian played by Jeff Bridges, was originally an eccentric and

semi-comical Italian attached to the Vatican library. Dino

rejected that person out-of-hand as utterly preposterous, and the

concept remains in only one line of the script. (Hint: look for it in dialogue on

Page 30 of this book.) [Semple Jr. is

refering to Prescott's line: "The rest of that log entry,

unfortunately, was suppressed by the Holy Office in Rome."~Blair] The reason I made our present

romantic

lead a comical foreigner was because the romantic lead in my outline

was Joe Perko, the oil-drilling foreman who remains in the movie only

as a bit. If I remember, I made Joe Perko the lead because I had

just read an interesting piece in New

York Magazine alleging that liaisons between classy

semi-intellectual female persons and roughneck blue-collar males was

all the rage. I didn’t believe that then or now, but it sounded

like it would make for an amusing relationship. One might well

ask by what lunatic fancy the girl of this script, Dwan, would qualify

as a “classy semi-intellectual”. The answer is, she was a

different person in the outline too: Camera Operator of a movie unit

along on the expedition to film TV commercials for the oil

company. Candy Bergen, that is to say.

With the exception of the change in the girl, the character shifts

described above were decided on instantly, almost by unspoken

assent. There’s a potent domino-effect in script

construction. The humorous Italian bit becomes a young Princeton

anthropologist, therefore latter is now your leading man, therefore

roughneck Joe Perko moves down the line, therefore the girl no longer

has to be Candy Bergen. It is not that I’ve got anything against

Candy Bergen: I’ve never met her, but I think she’s

terrific. The point is, there is something shamefully predictable and TV-ish about a beautiful girl

Camera Operator, which no amount of fancy footwork is going to get

around. The basic concept is unworthy of a gigantic ape.

When I grumbled about this, however, and suddenly had a flash that the

girl should be a nothing would-be actress found adrift in a raft, Dino

looked totally blank. Obviously he found it totally unbelievable,

with which it was hard to argue. It is unbelievable. But so, I

argue, is a 40-foot ape -- and having established “reality” of a sort

with the oil-exploration vessel setting sail, we needed a bridge to the

fantasy which will follow, and what more agreeable fantasy than finding

the most gorgeous girl in the world floating unconscious in the South

Pacific?

This whole question of “believability” and “reality” was the heart of

the matter -- greatly exacerbated, I must admit, by the phenomenon

which was occurring while we were hammering out our outline.

Phenomenon named Jaws.

Here was a picture filled with ludicrous absurdities, both

icthyological and otherwise, which was being accepted as totally real and because of that coining zillions. Dino

passionately demanded at the start that we make our ape as believable

as their shark. I tirelessly rejoined that despite the nonsense

in Jaws, it was so skilfully

done that people were willing to accept it as fact -- whereas nobody

would ever “really believe” in a 40-foot ape who flipped out over a

5’4” blonde bride.

Back and forth we went -- this abstract discussion concretized in

whether The Girl should be my Dwan or Dino’s hypothetical Candy Bergen

-- and God only knows how it would have been decided except that the

Director entered at that time.

Enter John Guillermin.

It is customary for writers to blame directors for butchering their

great scripts, and indeed that often happens, but certainly not in this

case. John is a little loony, as anybody would have to be to

carry off Towering Inferno

and King Kong -- I boast of a

certain attractive looniness myself -- but from the moment he read the

outline to the moment I am writing these words (just days before

publication), he totally dug the style of Romantic Adventure we were

after and busted his tail to keep that style coming through. I

won’t dwell on the nightmare problems of logistics and time pressure

which hounded us throughout -- that’s for another book -- but somehow

John survived them. There were plenty of hot arguments with Dino

along the way too, but in the end they were all resolved the same way:

at the bottom line, if the picture needed

it, Dino ordered it done.

(Maybe one exception to that, but that will remain our secret.)

I remember some smart-ass type around MGM, where we were shooting most

of the time, once telling me we were in horrible trouble because he’d

heard it rumoured we were on our third

costume designer. My own feeling was that that was exactly

why we were not in trouble

-- unlike most producers, Dino wouuld keep doing things over until

they were right. The picture was all that mattered. Res ipse loquitur.

However. Back to The Girl. Candy Bergen, Girl Cameraperson,

or the Actress Adrift? John liked the idea of the latter as much

as I did, and in the face of the combined opposition, Dino threw up his

hands. Try it. If he didn’t like it, he’d let us

know. As it turned out, he liked it.

I guess I did my first draft in about four weeks. It was easy to

write, which is always a good sign. It followed the outline

closely, incorporating the various character changes just described,

and again it was well received. Obviously, however, it was too

long. It ran about 140 pages when mimeographed, which would be

long for any movie -- and for a movie with so much non-dialogue action,

much too long.

Make it ninety pages, Dino says. John Guillermin looks

concerned. No problem whatever! I say. I’ll take it

down to ninety, lose nothing, and indeed improve it in every way.

John looks extremely concerned,

suggests that he and I go over possible cuts in detail before I do

them. I’ll have none of that. Just wait and see -- I’ll be

back in a flash with a terrific tightened script that will make

everyone jump for joy. So saying, I retreat to Aspen to execute

these boasts.

All writers are insecure in one way or another, and surely I’m no

exception. Unlike many, however, my insecurity doesn’t take the

form of violently defending what I’ve written and denouncing people who

criticize. On the contrary. When somebody implies something

of mine isn’t one hundred percent

PERFECT, I immediately feel guilty of having committed an awful crime,

having betrayed those who trusted me, etc., etc. I ruthlessly

throw out everything.

I was really delighted with the rewritten Second Draft, which finally

came out about ninety-two pages. I shipped it down to Canon Drive

for translation, following in person a couple of days later to receive

the expected pats on the head and congratulations.

Instead, I found utter shock and gloom. The Second Draft was

hated. John said everything that distinguished the outline and

First Draft had vanished. Dino opined it was impossible I could

have written such trash and actually accused me of having

sub-contracted the rewrite to someone else. All I could do was

mumble that I had, after all, only done as I was directed -- hacked it

to around ninety pages on Dino’s orders. “So why-a you listen to

me?” Dino demanded contemptuously -- and unanswerably.

Enough about what became known as “The Infamous Second Draft.” It

was discreetly chained in the attic like the batty aunt, never to be

mentioned again. John and I sat down quietly with the First

Draft, and easily processed it into something very closely resembling

the final script printed here.

Of course there were endless changes from January to October, 1976, as

the actual shooting progressed and the budget rose. Trim

this. Work out a substitute for that. By pure happenstance,

our KK was shot almost totally in sequence -- that is to say, the first

night’s shooting was Page 1 of the script, and the schedule followed

almost scene after scene to the end. There are some advantages in

that. When it became apparent, for example, that Jeff Bridges and

Jessica Lange played well together, John had me extend some of their

romantic scenes a bit. To compensate, we cut back on the

peripheral stuff like chitchat of the search party in the jungle.

The one area that drove us all nuts from beginning to end was what we

called the “Presentation Scene” -- where Kong is unveiled in New York

and makes his escape. You may remember, in the original movie it

was quite simple: the beast was unveiled on the stage of a theatre and

broke loose from there. We aimed at something more

spectacular. My outline and all drafts of the script had Kong

making his break from a huge spectacular in Shea Stadium. This

was easy to write, but would be much tougher to execute. Maybe millions of dollars tougher to

execute. There was also the point that two other big movies in

production that summer featured stadium panics -- Two Minute Warning and Black Sunday. Therein lies

this writer’s sole complaint against the producer in the entire

affair: Dino clearly indicated from the start that he considered

the stadium presentation infeasible, while John was insisting just as

strongly that it was indispensable, but never until much later did Dino

announce absolutely for sure

that we must find a substitute. Lest this complaint be weighed

too heavily, let me quickly add that no producer except Dino could have

made the movie at all -- that is beyond controversy. Anyway, as a

result of the diplomatic indecisions, midsummer found me writing

tentative variation after variation as the cameras ground closer to the

day….

Kong escapes from Madison Square Garden, which was only superficially

appealing.

Kong is landed by helicopter at a reception at the Bronx Zoo, from

which he escapes after also releasing all manner of beasts from

their cages.

Kong escapes from a Brooklyn pier, where he is being landed from a huge

barge.

Kong escapes from the Brooklyn Academy of Music, much as in the

original where he is being presented for the TV cameras.

And others.

The unfortunate part of the procedure was that we all became so jaded

and (yes!) bored with these variants that it became increasingly

difficult to sift the good idea from the bad. The chief

determinant of the way we finally did it was that it enabled us to

reuse the Great Wall of Skull Island, which still stood on M-G-M’s

desolate Lot 2 at a cost of nearly a million bucks. There John

worked out a sequence that was essentially a trimmed version of the

Shea Stadium of our First Draft, but still we were to be

bedevilled. Would you believe that residents of this Culver City

neighbourhood complained about the noise and so the cops made us shut

down at midnight? This despite the fact that it was a night

sequence, and in midsummer, it did not grow dark until nine o’clock.

However. So 1976’s King Kong was

scripted. It was fantastic fun. I’ve seen the picture in

rough cut, and the faithfulness of film to what I had in head strikes

me as amazing. I also realize the picture is emotionally rather

trickier than I’d thought -- forcing the viewer to love a monster he

first feared, rewarding that affection by killing its object in the

most brutal way, and not even sugar-coating this bitter pill with a

Boy/Girl clinch. I hope the concept doesn’t lay too much on the

audience. If it works, I will take bows along side Dino and John,

who made it happen. If it doesn’t, I’m not being falsely modest

when I say the blame is mine. Luckily, only those who read this

will ever realize that.

Lorenzo Semple Jr.

|

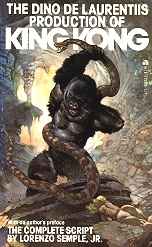

screenplay, by Lorenzo Semple

Jr., was published as a paperback, The Dino De Laurentiis Production

of King Kong. Included was a preface by Semple Jr.

recounting some of the trials and tribulations involved in

writing the screenplay. The preface makes interesting reading, so

I have

posted it here at Kingdom Kong.

screenplay, by Lorenzo Semple

Jr., was published as a paperback, The Dino De Laurentiis Production

of King Kong. Included was a preface by Semple Jr.

recounting some of the trials and tribulations involved in

writing the screenplay. The preface makes interesting reading, so

I have

posted it here at Kingdom Kong.